RULES REVIEW

Bloated and Unfocused System

The genre of the game is mystery, this is in the name of the development team (Agency of Narrative Intrigue and Mystery) and in the marketing materials for the series. This is not something the game leaves

ambiguous or relegated to third party materials. It is in the introduction and afterwards, frequently mentioned throughout the text.

The implications of this are that this game's primarily purpose is to facilitate roleplaying mysteries. Narratively, that is what it is for. Mechanically, it is not. The bulk of the mechanics are focused on

combat. The book is, as of writing, over 600 long. Large swathes of the text are dedicated to play opinions, such as what tense to use, facets of the setting and what mindset players and GMs should go into

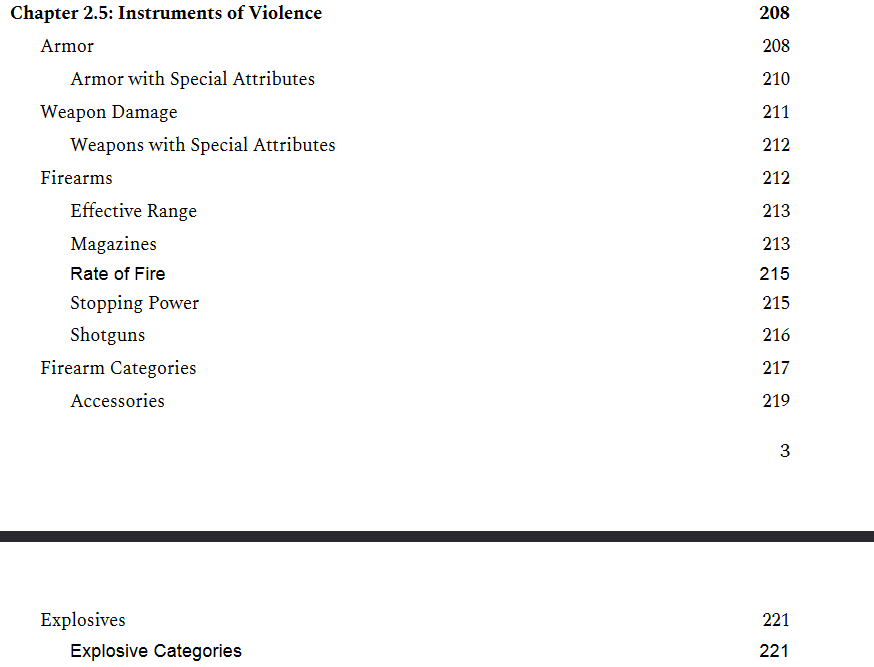

when playing. Removing most of these sections as well as random tables, 200 pages are dedicated to investigative rules and support for playing the game and 100 pages are dedicated to combat. Going deeper into

these sections, you will find that the investigation subsystem has far less complexity and also less depth than the combat subsystem. While both systems use the same core resolution mechanisms, almost everything

about investigations is used in combat (Fears, Truths, Traits, Composure, Contextual Modifiers) and combat adds even more detail. Weapons have different damages depending on what they are, have different abilities

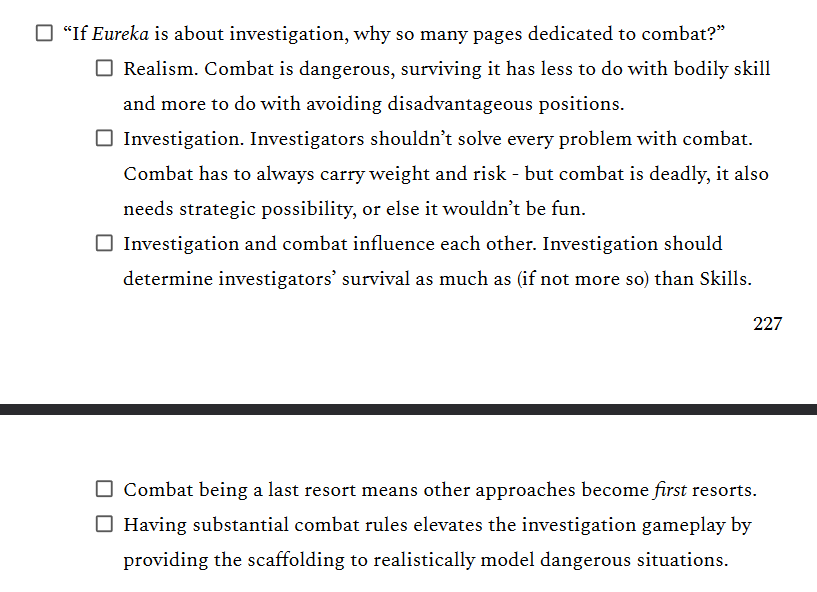

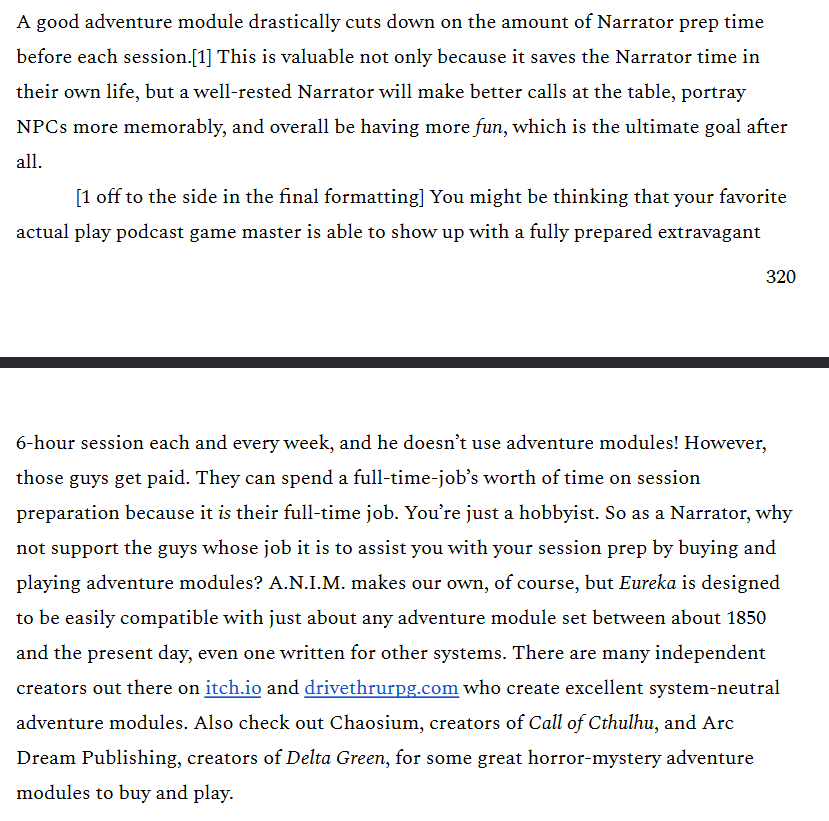

depending on what they do and the two separate forms of health add a layer of complexity on top of all that. I haven't included a full picture of the table of contents because it is 10 pages long but here are the

categories of weapon and armor.

The monstrous character primarily receive benefits through violence. They kill to survive and can not be killed themselves. They usually have super strength or curses or similar abilities that allow them to

deal massive amounts of harm to people very quickly. Some Traits focus on combat instead of investigation, using action movie and game touchstones as references. Indeed, much of the touchstones of the book are

actually action orientated series. Resident Evil, Hotline Miami (as shown in the picture below), John Woo movies. These games and films are not mystery nor do they try to be. The primarily means for interacting

with the world in those settings is to kill things. I am not against that! But that is not what this game is supposed to be.

Most notably, there is no narrative resolution described for solving a mystery within the text. However, there are plenty described for wounding, taking out or killing people. When I play a mystery game or

read a mystery story, the most important part is the denouncement. This is the action that defeats the culprit, the recognization they you figured out their tricks. In Eureka, the resolution that is mechanically

supported is fighting them. Sure, the GM can write a module where you go and point at the culprit and the culprit limps off to the woods to lick their wounds, never to be seen again. But you can do that in

Pathfinder too. In Pathfinder, there is nothing stopping you from running a mystery where you use skill checks to find clues and then going and fighting a large monster afterwards. This is not the recommended

mode of play but it also is not prevented. Eureka does have advantages of Pathfinder in some ways, the Composure system and the Eureka points support investigative tactics. To a point. At the end of the day

though, you fight or run away from something frightening. A gangster, a serial killer, a vampire with teeth like peaks of ice. You do not receive the catharsis, mechanically, for solving the mystery. Only

from surviving the encounter.

The game describes combat as lethal, suggesting it's to be avoided, but in practice, a lot of the fun "toys" are gated behind combat. So too is a satisfying narrative resolution, playing the game as presented.

Monstrous characters can rip and tear their way through human enemies who can do nothing to them and have a massive advantage over human PCs in monstrous combat too. Special rolls and rule variants are only

accessed through combat situations. John Woo's films are infamous for how cool and interesting the gunplay is and designing an entire mechanic around his works tells the players that they can and should be

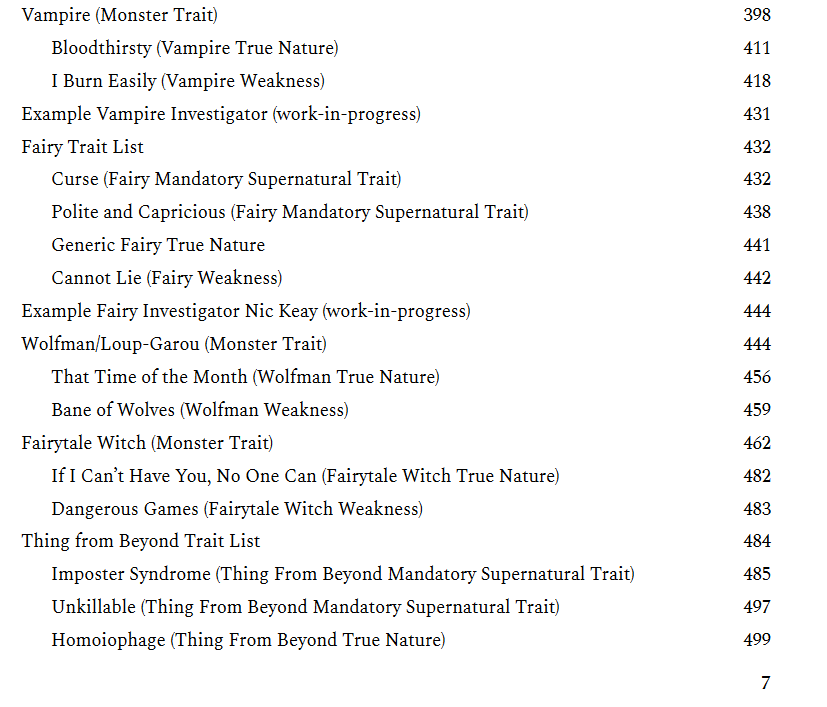

getting into gunfights. The creators know that this is an issue so they write an essay, before describing the combat rules proper, on why combat in Eureka is justified. However, this does not address the actual

concerns about how combat is presented in the narrative. Instead, it takes a stance of "the combat is fine and you are wrong if you think it isn't". This overly defensive, pre-emptive response to criticism is

featured frequently throughout the book. It makes the reader feel as if they are reading a review of somebody else's book rather than Eureka.

My response to the above is simple, if the game isn't about combat then combat should NOT be fun! Rolling a few dice and then dying is a perfectly acceptable scenario. Players should be aware at all times

that something they are doing may lead to risks and then they can either mitigate those risks using stealth, investigation, social skills, resources, etc or not do it. The fall back option of getting into

exciting gun fights with highly defined gun rules and cool magical powers is rewarding combat, it is encouraging it. Combat does not feel lethal or punishing. It feels like the only way you get to have

the full experience of the game. It is the nature of a player to want to experience everything a game has to offer and so, they will choose to enter combat. Actual Plays of Eureka reflect this. Including

the campaigns designed by the creators themselves.

Ludonarrative Dissonance

The most severe issue in this game and the source of all symptoms above is ludonarrative dissonance. The mechanics do not support the narratives presented by the authors and because so much of the book

is about the authors' opinions on optimal play, the divergence between the two become more prominent. While the combat system is bloated, the issues would remain to a degree even if the page count was

cut down and most of the rule variants were stripped. The fact that combat is emphasized as a resolution method instead of a failure state is a failure of design. Being able to use your pistol and shoot

out an enemy's pistol is described in the book. Pointing your finger at the culprit and exposing them and what happens after is not. Indeed, there is no real section devoted to creating NPCs at all and the

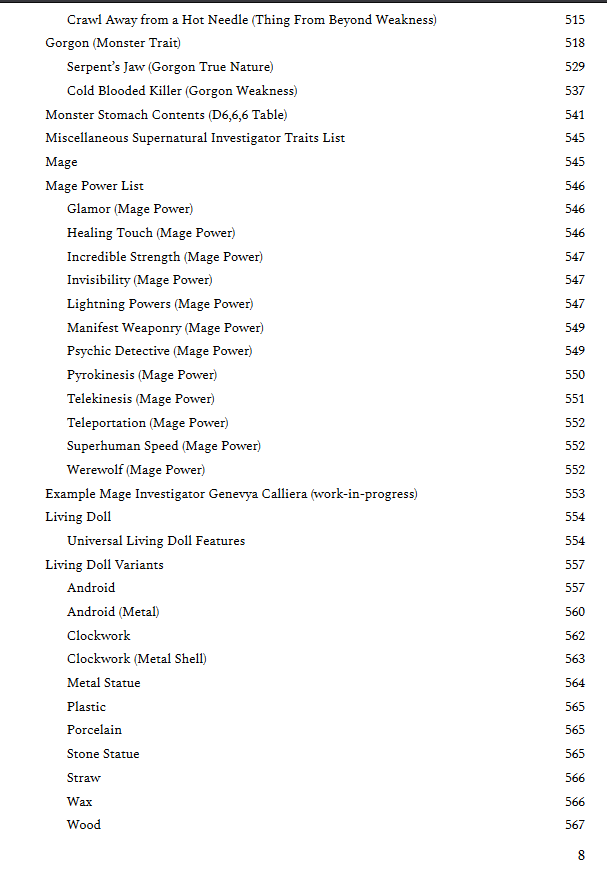

section on creating your own mysteries is fairly barebones. The game instead recommends that you repurpose modules from other investigation games. In a sense encouraging you to go and play Call of

Cthulhu or Gumshoe instead of Eureka.

As a side note, I particularly dislike this section because it reads as an ad read. The part in a podcast where they stop everything and tell you to buy their proprietary dice. Telling people to go and buy

products it not supporting GMs in creating mysteries for your setting. Adding rules, suggestions and support within the game's book are.

The narrative dissonance between the tone / genre and the mechanics is further widened by the playable monster characters. Monsters are supposed to be rare, secret and dangerous. Players can play them

with no restrictions. These monstrous characters have more ways to interact with the world, both inside the party and outside, that human characters do not. Monsters' terrible hungers add a pathos and

drama that is not avaialble to human characters. There are no mechanics for mundane addictions or social issues nor are there for playing a mundane serial killer or other such criminal, who might feel

a similar drive and need to go forth and kill and keep killing. Monsters have supernatural abilities and humans do not, as magic is not something a character can learn in the narrative. There are a large

variety of different monsters, with different abilities and needs, and many of these monsters have sub options. There are no such variants for humans.

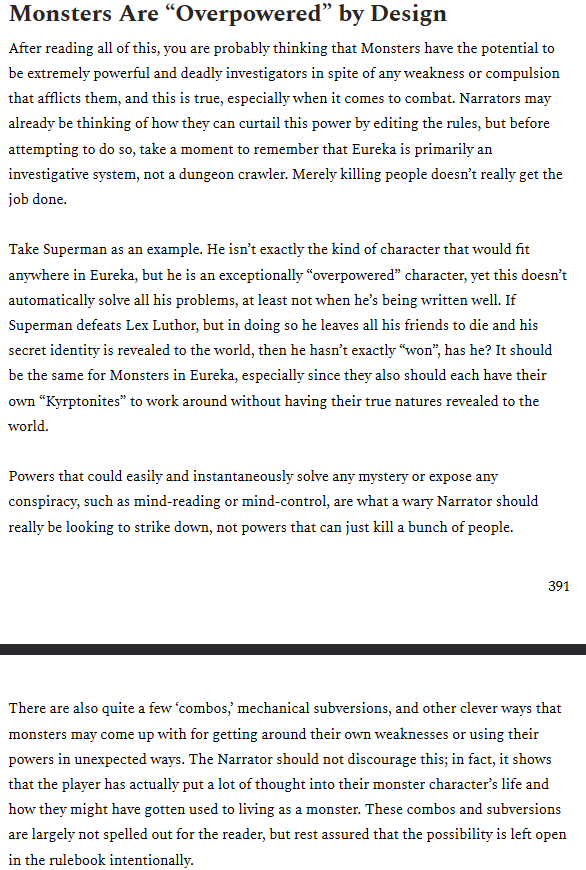

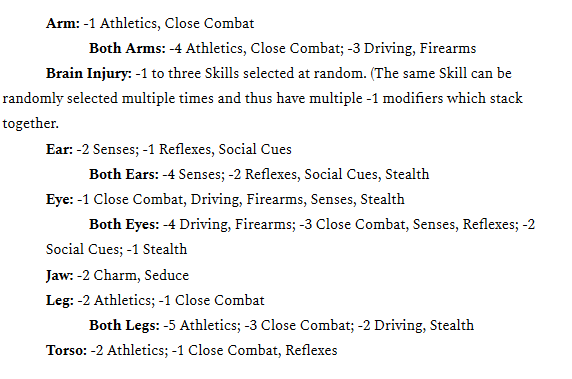

Monsters are supposed to represent specifically physical disability but have more ability than human characters mechanically. They are explicitly described as "overpowered".

Disabled humans on the other hand have realistic disabilities that negatively impact their ability to investigate.

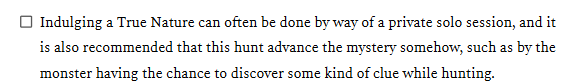

Monsters get special scenes dedicated to satisfying hunger, secret from human PCs.

The variety and depth, narratively and mechanically, that playing a monster provides has no equivalent nor attempts at equivalency with human characters. Players with human characters simply have less options

than players with monster characters. Ironically, this better reflects the experiences of disability than the narratives presented through the monstrous characters. In the style of game that Eureka is,

this is a bad thing to do to players. The game is lethal, it's deadly, characters are expected to die. Introducing characters that can not die through any means, who are stronger and can do more than human

characters is telling players not to play humans. A player can be expected to optimize their gameplay. The greater the risks, the more optimization happens. This is not the fault of the players that this

happens. It is a flaw in game design.

More on the topic of monsters and privilege in Eureka can be found in the section Game Identity.

Minor Quibbles

This is a short list of things I don't like. These are mostly pet peeves with stylistic choices that have no real effect on the gameplay or narrative. Feel free to skip this and go right into Game Identity.

Upon opening the section for Composure, you are greeted with a rather nice design of little detective breaking into puzzle pieces and flying away. Below that, is the explanation that Composure is emotional HP.

It is not sanity. According to the authors.

Functionally, it doesn't matter what the opinion of the creators are. Most games with psychological or emotional damage use a similar system and they call it sanity. You lose it when encountering terrifying or

painful things, you regain it through being comforted by a friend, monsters use it as a secondary health system (bringing to mind World of Darkness). If a character loses all their Composure, they are expected

to be roleplayed in a manner reflecting instability.

The refusal to commit to what this system functionally does manifests mechanically. The game simply encourages players to behave differently. There is no mechanical benefit for doing so nor mechanical detriment

to not doing so. The mechanical benefit of Composure is a reduction to your rolls. This could function as an exhaustion system by removing this section entirely and simply letting players conclude that the result

of not eating and being terrified for days on end is being too tired to perform even tasks they know well correctly. Then, players are left to their own devices as to how much it is sanity and how much it is

a measure of exhaustion or stress.

A lot of the Traits and chapter headings are tongue in cheek references to nerd culture which takes away from the serious atmosphere the game is trying to portray. The setting does not feel serious. Constant

references to Scooby Doo, Star Wars, the X-Files and internet memes litter the book. In other places, the terms are oddly childish for how mature the game supposedly is (described as an R rating setting).

"The Creeps", "Woo Woo", "That Time of the Month". This doesn't effect anything and you can simply ignore it but much like how I don't enjoy ordering a "Rooty Tooty Fruity" pancake at a restaurant, I would not

enjoy saying "your Woo Woo trait allows you to--". At least at Denny's, the restaurant is family friendly.

The reference overdosing makes it more blatantly unfair that there aren't any black cultural touchstones in the series. The creators personally informed me that Cleopatra Jones would not fit the setting

but all of this other stuff does, apparently. The little detective art has plenty of poses and designs of famous detectives but we were not afforded so much as a single Afro Detective. It would be silly! But

the book is already silly!