RULES REVIEW

On the Three Pillars

As befitting a neo-traditional game, Changed Stars uses the Three Pillar Experience as a play guide. If you're unfamiliar with this terminology, it is a school of game design and thought that positions roleplaying,

combat and exploration as the bases of which TTRPGs are built upon. While this was formally cofidied in Dungeons and Dragons Fifth Edition, this is how neo-traditional games have been played for nearly thirty

years now. Those of you who have played Deadlands or any individual World of Darkness game likely recognize this already. Changed Stars does a little more than imply its usage though; it outright supports it. Not

only are there mechanical benefits to exploration, which are not usually present in neo-traditional games of this era, there is also an expansive gamemaster's section which clarifies the authorial intent of the

book.

It is common in neo-traditional games to use the Three Pillar Experience as a play guide rather than a design guide. Rather than ratifying the three playstyles within the text itself, it is left to the table to

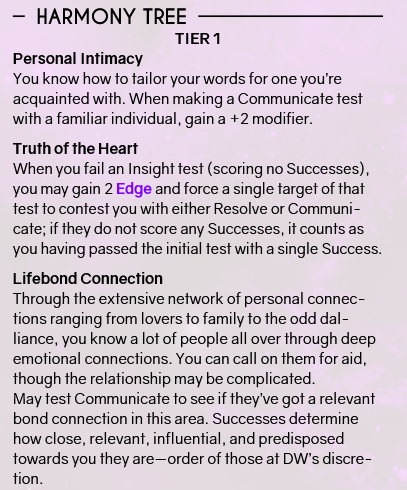

implement them. Instead, these games provide rules for combat and possibly exploration. If social mechanics are included at all, they are relegated to the realm of "your roll against my roll", which is not an engaging

form of play. Changed Stars tries to be the exception to this and fails. The game intends for there to be validity for all playstyles and resolutions but in practice, the mechanics push players towards combat.

Players seek to engage with the game's mechanics. These are the space on which the game world is built around and where skill mastery is expressed. Therefore, the more mechanics that a system or subsystem has, the

more likely players are going to focus on it. In the case of Changed Stars' combat, not only is there a clear and broad base system, there are also several subsystems layered on top of it. Ships are disabled by

destruction, medical emergencies created through injury and the majority of character creation options are about either bringing violence or supporting it on the field. There are various stat blocks for creatures to

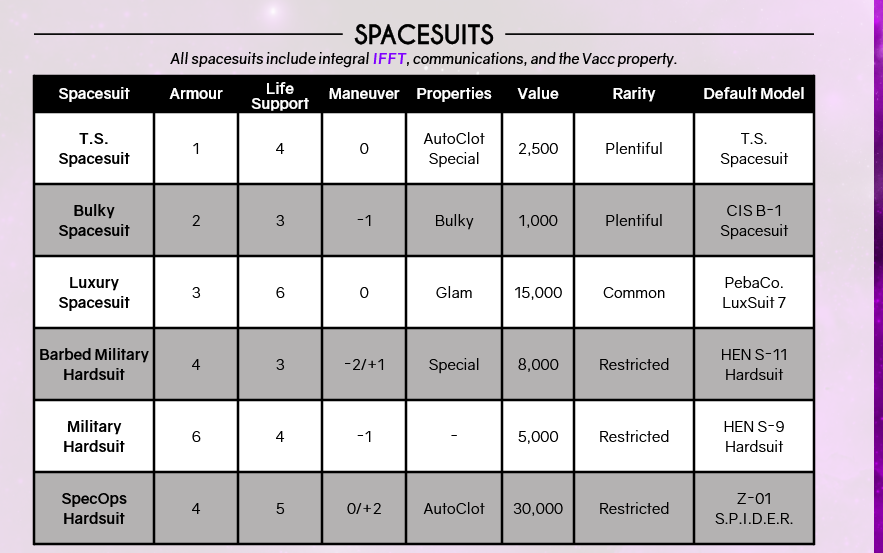

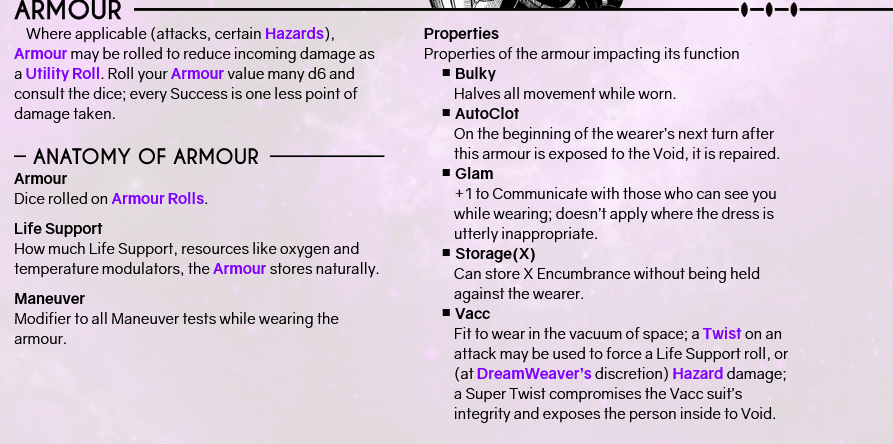

fight, guns to fire and locations to evade in. Within the equipment armor section, only one sample spacesuit has any social benefits and only in the form of a flat +1. Altogether, this forms a picture; the majority

of encounters will be resolved through violent conflict.

I do not have any issues with violent combat in games nor do I with a game that focuses on it. The issue arises when a game wants to support other playstyles but fails to give them anywhere near the same mechanical

depth as combatative play.

That said, Changed Stars puts in more effort to accomodate alternative play than their contemporaries in the genre. First, players are given the option to create noncombatants. These characters are not useless and

can provide mechanical support in fights, though they usually won't be able to participate in them as directly as others. This may sound to some as a punishment. It is not. There are plenty of people who thrive on

playing support characters in MMORPGs and so is true in the TTRPG realm. By allowing these players to take control of social scenes, in whatever number they may be present, and also participate in the game's main

conflict resolution, it gives a little space for diplomatic characters.

Second, there is one mechanical subsystem that the social system has and the combat does not. This is the Cope system.

Because a Shock can occur from any roll that accumulates too much Shock, it is vital to the wellbeing of player characters (and the party) that there is relief for this. While it is possible to participate in play

without having a party member who specializes in this, the party is worse off for it. The ability to get a specific type of negative or positive coping mechanism and the fact that these have a real, mechanical

effect on play adds a dimension to social skills that other games in this genre have ignored. While I wish that the social skills and diplomacy mechanics were more robust, with more mechanical variety, I can see

the direction that the game was going for.

A Thousand Ships

Now onto the meat of it. My biggest complaint with the system itself is what was present and what was not. When it comes to the structure and form of this game, I found it more than adequate. Yes, it is true that the

base combat system is familiar to me, and it will be to anyone who has experienced more than a handful of TTRPGs. But there is is a reason why this type of system is commonly used. It's good and it's fun. Players

understand what they should be doing and what they want at nearly all times. It's a system that tells everyone where they stand, how they can act, what a desirable action is and provides ready feedback for success and

for failure. Changed Stars adds further tactical interest on its own rights with the inclusion of talents and edge breaks, which players are free to take on character creation. These additions add an element of resource

management and "cool factor" that less complex games often lack.

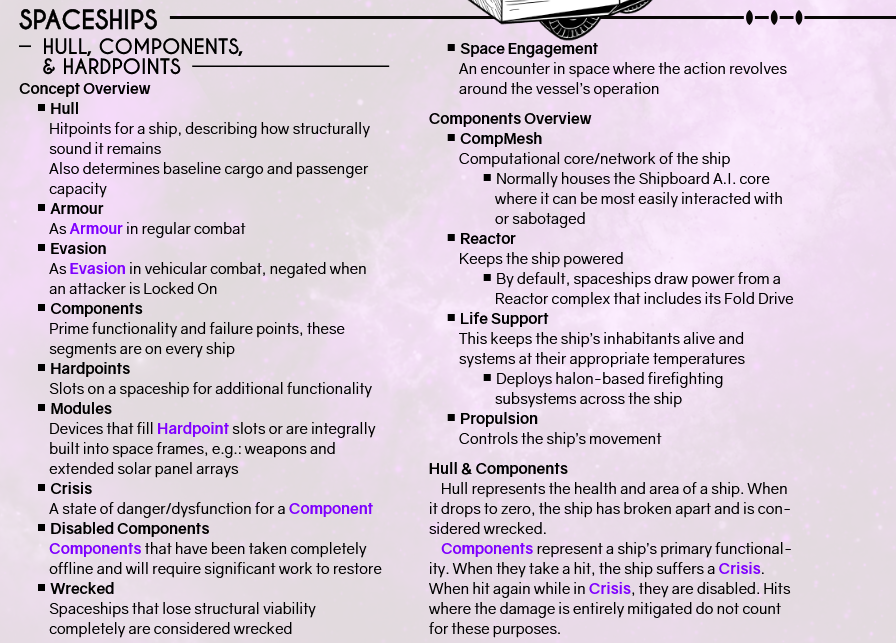

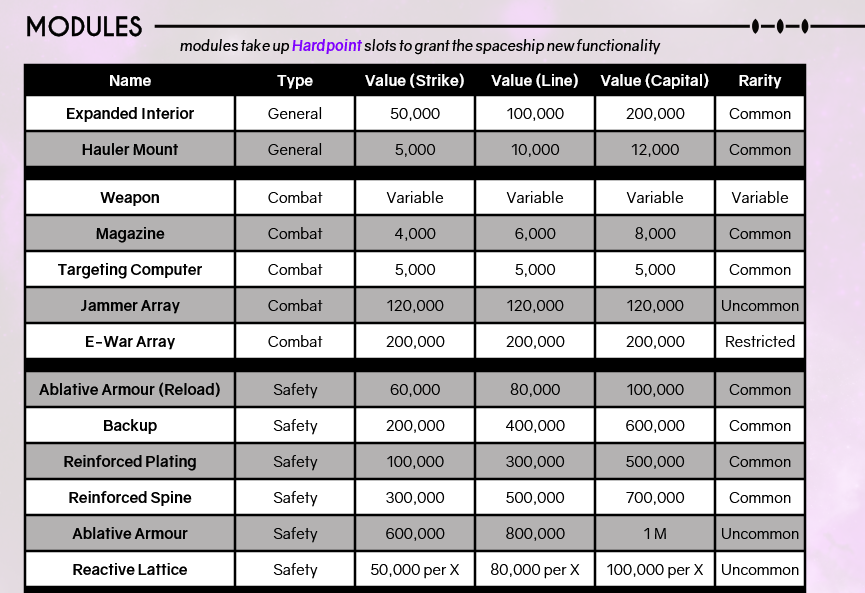

The game's greatest, mechanical, strength is the ship system. Other spacefaring games treat ships as an extension of the player characters or another player character in its own right. The same mechanics, perhaps

renamed, that a player character uses to run fast and hit hard are reycycld to drive fast and shoot hard. Changed Stars does not do this. Instead, it introduces to us a separate subsystem, where each part of the ship

is a valuable component with its own skills.

There are a number of reasons why the spaceships struck as particularly engaging. First, they are intuitive. It logically follows that if something that gives you the ability to perform x is destroyed, you can no

longer perform x. In games with subsystems that do not resemble the base system, confusion often sets in. By making the system follow what we in reality would imagine to be "correct", the components evade this

confusion.

Second, this opens up a lot of mechanical depth. What are we targeting and why are we targeting it? What happens after we destroy it? Can we destroy it this turn or should we focus our efforts on another part? Not

to mention the tension that could arise from targeting a component or hardpoint that you believe to do one thing but in actuality does another.

Finally, it is fun. Customization is a popular topic in gaming for a reason. It is satisfying to get to influence the game world, it's the reason why a lot of people play. Neo-traditional games are known for their

high character customization. Most of these options are related to combat, yes, however they are still valid options and make every player character feel different. When these options extend to non player characters,

they contribute to the longevity of a campaign as they let players explore many different tactics over time. Not only can you customize your character, you can also customize their ship. Buying a new part can completely

change your strategy for surviving firefights. That's something you just like to think about.

Everything Else

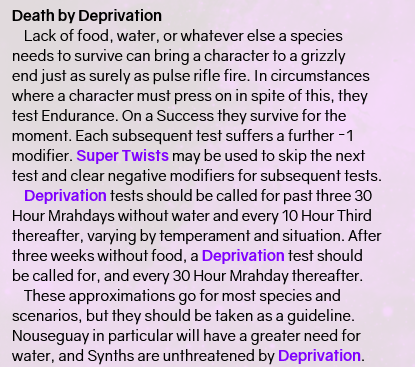

Within the game's design space, there are also survival, hacking and medical subsystems which all have varying degrees of breadth and depth. The inclusion of this is warranted. Between the narrative and the mechanics,

the game paints a picture that this is a game about skirmishes battles on the edge of the known world. Whether players can obtain medical care or even basic provisions depends heavily on where they are, what they are

doing and who they are with and it is clearly the intended mode of play that sometimes, they simply do not have enough. Adding subsystems for these facets increases engagement with the narrative. Rather than relying

on individual tables to decide what the effects of starvation or air hunger should be, the game tells us and takes the burden off of gamemasters. The game would certainly be poorer without the inclusion of these

mechanics and the survival system is far superior to what a number of major label TTRPGs have to offer.

Order of Arrival

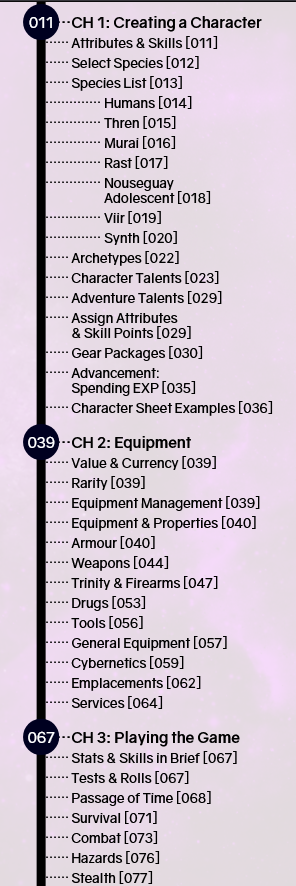

Now, onto the structure of the book itself. There were notable issues with the way that the book is formatted which caused initial confusion. It took me three readthroughs to properly understand the rammifications

of the character customization options. To better explain, it is traditional for TTRPGs to open with the character creation section in the indie realm. But these books do not have the depth nor the complexity that

Changed Stars has. Not to mention that most of those games use pre-established terminology such as skill, movement, charisma, power and so on. When reading through the Creating a Character and Equipment sections,

I had no idea what Copes, Shocks and Edges were nor did I understand their significance. It took nearly seventy pages to get an explanation and by the time I had reached that section, I had already forgotten much

of what I read from the other two chapters. Ultimtely, I ended up opening a second copy of the PDF. One to reference the character customization options and one to reference the game rules. It is clearer for a

mechanically dense game to have the character creation and equipment sections come after the rules section and this is how the book should have been structured.

On Gamemasters Sections

But I did like the placement and overall structure of the gamemaster's section. It's uncommon for independent TTRPGs to include this section at all, instead allocating a page towards instructions or assuming that

the gamemasters who pick it up will already have a knowledge of how to run the game. Those that do include these sections often go too far. Personal opinions of the authors mar the section, rendering it unreadable

as the focus is on obscure things like "what tense should be used when playing" or overly controlling like "this is what you should think about the game". Both of these authorial reactions stem from the same source,

the desire to not be criticized. When you avoid instructiing gamemasters, you can say that any failures of the game were failures on them to run the game. When you overly instruct gamemasters, you can say that any

failures from the game came from deviations of the script. Changed Stars' gamemaster section is without illusions. The section is written to advise gamemasters on how they, and their players, can get the most

enjoyment out of the game. Never does it take a condescending or fearful tone.

Furthermore, everything in the section is useful. Within the twenty five or so pages, gamemasters are given backing on the game's authorial intent, advice for how to structure sessions and campaigns and aids to

make their jobs a little easier. From thereon, a sample adventure and beastiary (both their own sections) provide further instruction.

It is understandable that independent TTRPGs would have difficulty with this section. The creators of the game already know how to gamemaster it. It's their own invention. And it lends an increased development

time for something that fewer people receive benefits from since, after all, most independent TTRPG fans are already familiar with the basics of TTRPGs. But that's why I find it all the more impressive that this

section was included in the way that it was. I think that this section is worth reading by every game designer so that they can see what an independent gamemaster's section should be like. With variations depending

on the narrative voice, design goals and mechanics of the game, of course.